Category: Uncategorized

St. Boniface

St. Boniface

Other Voices

It can be difficult to find Indigenous voices in the surviving archival records relating to the school, and the school’s closing date, 1905, makes it very unlikely that any Survivors of the St. Boniface Industrial School are still alive to share their stories. But despite this, the children who attended the school and their families have left a record of their experiences with the school in the history of the school itself.

Throughout the St. Boniface Industrial School’s short history, it was chronically plagued with difficulties with recruiting students, and with runaways. Through their actions, students and their families left a record of their experiences at the school, and of their resistance to the school and the system that it represented. Following are some extracts from school records that reveal this history.

Additional Resources

Ressources supplémentaires

St. Anthony Orphanage and Boarding School

Jesuit Seminary

Jesuit Seminary

Collège-des-Jesuites

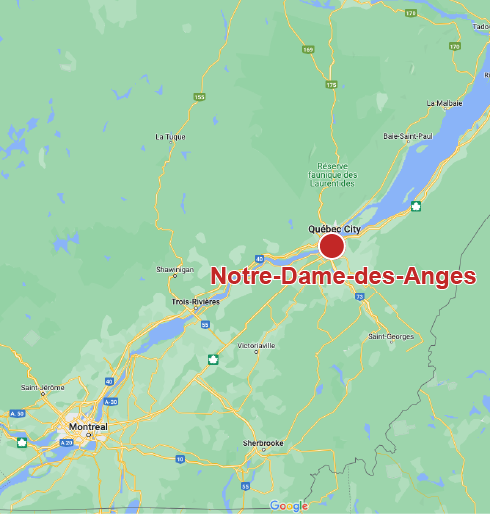

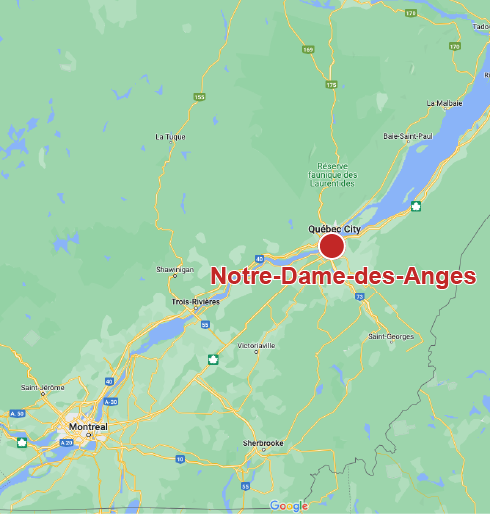

Notre-Dame-des-Anges

Society of Jesus (The Jesuit Order)

1635-1640

In Other Words

The Jesuits, writes Jackson in her article “Silent Diplomacy: Wendat Boys’ ‘Adoptions’ at the Jesuit Seminary, 1636–1642,” “hoped to use the school as a tool of conversion, with the expectation that students would then return home to Wendake to bring others to the Catholic faith.” The Wendat, on the other hand, sent a small number of their children to the school not to be converted to Catholicism, but to “facilitate a friendly relationship between the Wendat and the French.”1

The Jesuit seminary for Wendat children at Notre-Dame-des-Anges lasted a brief six years, opening in 1636, after the Jesuits had met with Wendat representatives to discuss forming the school. For their part, the Jesuits hoped that the seminary would be a way to encourage the conversion of the next generation of Wendat leaders to Catholicism. These leaders would, in turn, the Jesuits hoped, return to and convert their home communities to Christianity. As Jackson notes, “they would be disappointed.”2

The Wendat had a different view of the school and their participation in it, Jackson argues. They “responded in hopes of forming a friendly, long-term relationship with the French.” For some Wendat youth, attending the Jesuit school was a way that they could participate in the political life of their community by facilitating this kind of relationship.3 “As the [Wendat] boys immersed themselves in French culture at the seminary and committed to practicing the principles of Christianity, they believed they were joining the French community, mirroring Iroquoian adoption practices,” writes Jackson. “The Wendat considered adoption, or creating a fictive kinship bond, to be a diplomatic act. They saw the relationship between the boys and the priests at the seminary as a key part of a larger political undertaking in constructing French-Wendat diplomacy.”4

“Historians,” Jackson adds, “have traditionally taken the Jesuits’ point of view and interpreted the school as a vehicle for failed conversion or education,” but framing the project in terms of “success or failure, does not do justice to the complex motivations for all involved with the school.”5 Approaching the short history of the school through the lens of Wendat diplomacy rather than through religious conversion, Jackson focuses on the school’s first two years. Although “the seminarians’ words were rarely recorded in the Jesuit Relations,” she writes, “careful reading provides some insight into their thoughts and motivations, and indicates that the boys were active participants in their (re) education.”

Seen through this lens, the seminary, Jackson argues, gave its Wendat students “an opportunity to help their communities.” Although they had not yet lived long enough to have earned leadership roles within these communities, the boys Jackson follows in her study used their agency to agree to live at the seminary; in this context they could also choose to abandon the project. “Ironically,” she writes, “their agency was mostly manifested through their apparently passive acceptance of new lifestyles at the seminary. They wore French clothes, ate French food, spoke and read in French, and prayed as French Catholics,” putting aside their own cultural identities for the time that they were in the school for the sake of the success of their diplomatic project. While much of the diplomacy the boys practiced was silent, the success of their efforts can be read in the ongoing relationships between the Jesuits and Wendat. “The Jesuits remained in Wendake until the Wendat dispersal in 1649, but the Jesuits and the Wendat maintained a close relationship even as they relocated,” concludes Jackson.6

Additional Resources

Ressources supplémentaires

Shirley Flowers

Shirley Flowers

Labradorimiut

Originally from Tikigâksuagusik (Rigolet)

Inuvialuit Settlement Region

In Her Own Words

In the early 2000s, Shirley Flowers contributed her story about attending the Yale School to the Legacy of Hope’s “Where are the Children Exhibit, a touring and online exhibit curated by Iroquois artist Jeff Thomas. The exhibit looks at Canada’s Residential School System through archival records and Survivors’ stories. The following is taken from a transcript of her video testimony, a part of the exhibit. In this testimony, Flowers describes her experiences at Yale School.4

In one part of her testimony in the Where are the Children Exhibit, Flowers describes the regimented routine at the school, telling the interviewer that

A. Depending on what you were doing, I think you had to get up at 7 maybe —

— Speaker overcome with emotion

We had to do all the chores. If we worked in the kitchen we had to get up and get the breakfast ready and look after whoever you sat with at the table. I was thirteen and I was considered a bigger girl, so we had to serve the boys, and little ones, whoever was at our table.

We had to do our chores throughout the day because we maintained it. We did the cleaning and everything.

At night time we were set aside for studies. We had little time to be free or out to do whatever.

Asked about the food at Yale, Flowers remembered that

A. There wasn’t enough. I learned to steal. If it was my turn in the kitchen I stole, and I stole enough for other kids. Some of the stuff I had never seen before because I was used to eating wild meat and stuff like that. I didn’t like it.

A. In the dorm there were about seventy of us, I guess. There were 2 buildings. One was for little kids and the bigger one, where I was, housed the bigger kids. But even in there they were separated into big girls and little girls, whatever. It was age groups, probably from age 5 to 17 sixteen, seventeen, whatever.

Flowers recalled her experience attending Residential School as “frightening,” telling the interviewer that

A. It was frightening leaving home. I think for me some of the stuff came before I left, the dread of it and seeing my mother crying when my siblings left. I think I was impacted before I went. I remember seeing some of that, and seeing my brothers and sisters coming home and they were supposed to be my family but they were strangers. They came home strangers and we were related to each other.

And then knowing I was going into — Some of the stories people told, the tough work, and whatever, not being free and not being able to have contact with home was scary. I was always scared someone was going to die and I may never see them again or get to them before they would die, before I could get home.

Q. Can you talk about the time you ran away and how that transpired? What made you want to run away?

A. Somehow even when I was little, like I was telling you, I seen my mother crying, I knew that there was something not right. I’m thinking there’s something wrong. They can’t take us and put us away like that. I almost felt like I was in prison when I was there. They can’t do that to me.

Talking about running away and returning home, Flowers recalls that

Q. Did you get caught after you ran away and made to go back?

A. No.

Q. Did you go home?

A. I went home.

Q. What was that like, going back to your mom?

A. It was good. I went home. I stayed home that year, but I went back to school after that and finished.

In 2011, in her testimony to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Shirley Flowers told the Commission that “The residential school was part of a bigger scheme of colonization. There was intent; the schools were there with the intent to change people, to make them like others and to make them not fit. And today, you know, we have to learn to decolonize.”5

Additional Resources

Ressources supplémentaires

Emma LaRocque

Emma LaRocque

Plains-Cree Métis

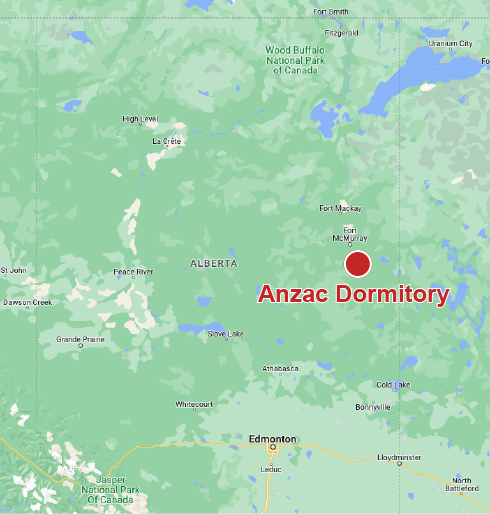

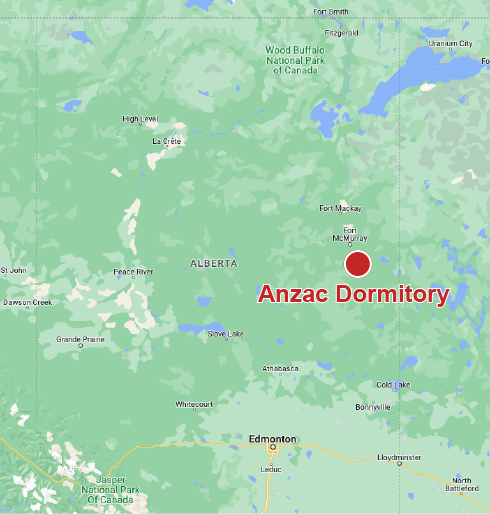

Originally from northeastern Alberta

Attended Anzac Dormitory, Alberta

In Her Own Words

In her essay “Me and Mennonites: The Way We Were ‘The Other,’” Emma Larocque writes about the complicated nature of her experiences while living in the Anzac Dormitory as a teenager. Reflecting on her experiences at the Dormitory, and after she had left it, she notes that many of her experiences at the Anzac Dormitory were positive, especially coming on the heels of a period at school in Lac La Biche where she experienced rampant racism. But despite this, Larocque writes that her experiences never were simple. “Not everything went well for me or my friends or my brother at the Dorm,” writes Larocque.

There were at times misunderstandings, cultural conflicts and power struggles between the children and the staff. Perhaps these were unavoidable, but these were power struggles that the children could not win. The majority of the staff were very young and obviously knew next to nothing about who we were, especially that we were quite diverse in our cultures and languages. Being mandated to missionize, they were eager to indoctrinate us. And given the White American mass-produced and ideologically based stereotypes about “the Indian,” I suspect they came with a lot of pre-conceived notions and themselves suffered culture shock.

Years later I read a missionary-type report that one of the staff had written. It was a classic colonial gaze at “the natives.” Interestingly, colonial gazing is apparently not over. I just read a long article by T. D. Regehr in the Journal of Mennonite Studies, in which the Anzac Dorm children are basically objectified and “ethnographied” (my word), which in post-colonial language is known as “othering.” However, we are now reversing that gaze.

For me, overall, the Anzac Dorm Mennonites proved to be the nicest white people I had met up to that point in my life. I hung onto that–and their values–for dear life! Having suffered the trauma of the brutal racist environment of the LLB [Lac La Biche] school, I was indeed easy pickings for kindness and indoctrination.

The kindest of all the Dorm staff were Harold and Erma Lauber from Tofield, Alberta. I adopted them. And their faith. When school was out I visited them at their farm near Tofield, some 45 miles east of Edmonton. And when I was going to high school at PBI [Prairie Bible Institute] I would come and stay at their place during holidays, as I could not afford to go home to see my parents. At Harold and Erma’s, always I felt welcomed, safe and well-fed. And I didn’t mind working with and for them. Gardening was not strange to me, as my parents had gardens whenever possible. But herding cows was strange–and terrifying–although their good dog did most of that for me! Hard work was not strange to me, as I grew up watching my parents model a very strong work ethic. People of the land know how to integrate work with life. I also went to the country Salem Mennonite church with them, and got to know a host of wonderful people, many related to either Harold or Erma, and gained many friends from that community, too.

The bond between me and the Laubers was extraordinary. It was not financial; the connection was purely human. There were vast differences between us–in age, culture, belief systems–to say nothing of economic standing. Due to my educational pursuits I had to leave my parents long before any child should have to leave their parents in order to go to school. Those were very difficult things to do and go through. But what made it tolerable for me was having people like Harold and Erma as my stability zone in my teenage years. That sort of gift is immeasurable. And it is forever.

Reflecting on her experiences with a number of individuals and institutions that began with her years at the Mennonite-run Anzac Dormitory, Larocque writes that

I have no institutional affiliations with the Mennonite church, nor am I a member of any church. And I certainly have noticed that invitations to speak at Mennonite events or churches have totally disappeared. My association and relationships with Mennonites has been more personal than institutional or ideological. While I respect the Anabaptist vision with its core values, it is my Metis cultural tradition and my own intellectual preference to relate to the Mennonite tradition on personal terms.

My relationship with Mennonites continues today in very personal ways.

Further along in her essays she writes that

In part because so many special Mennonite individuals have made such a difference in my life, I have always tried to make a difference in the world I live in. My hope for the Mennonite Church is that it not lose its Anabaptist roots and human values, which is what makes it unique and puts it in a position to reach across cultures and nations for service and non-violence. The world needs an alternative ethic, alternative to hatreds born out of implacable leftist and right-wing ideologies. My hope is that it not succumb to the fundamentalist movements in the Evangelical churches sweeping the United States.

I also hope that the Mennonite community will not forget on whose land they stand–that they will seek to understand and to support Indigenous peoples’ struggles for justice, land and resource restitution.

Additional Resources

Ressources supplémentaires

Mike Durocher

Mike Durocher

Métis

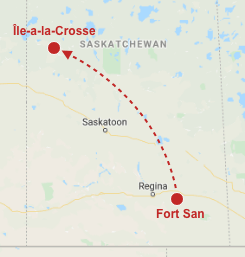

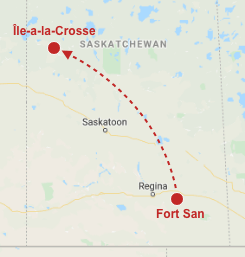

Born in Fort San TB Sanitorium near Qu’Appelle, Sask.

Attended Ȋle-à-la-Crosse, Sask.

In His Words

“Most of us started school in Grade 1 and when we were seven years old. Our parents were very reluctant to let us go to school any sooner. Ninety-nine per cent of us spoke only Cree or Michif-Cree, so nobody spoke any English when they first went to school. It was very difficult. I mean, the school was good — you learned your ABCs — but the school was run by the Catholic Church, the Diocese from The Pas, and the nuns and priests all spoke French. If you got caught speaking Cree, then you got disciplined. The first couple of times, you probably got a lecture and a good scolding, and beyond that they would start giving you the strap. It was very strict Roman Catholic.

Basically, the church ran the town. You went to church on Sundays. I was an altar boy from when I was little, so even in the residential school I’d get up early in the morning, go to church and serve mass, then go have breakfast and go to school. We didn’t miss Easter, Christmas, all the special religious functions. We were always part of it. There was no excuse to miss.

All the students that came to Île-à-la-Crosse from La Loche, Turner Lake, Wollaston, Big River, Dore Lake, Sled Lake, Dillon, everywhere, they were all non-status Métis. All our treaty cousins went to Beauval for the treaty school there. In Beauval, it was a federal school so, the feds looked after that. In our case, it was more run by the church, but it was the same education system. So, the ongoing issue now is who’s responsible: the federal government, the province or the church?

Well, all of them in my opinion. They all had a piece of it. We were lucky because our community, Sandy Point, is about 5.5 miles from the school. One of our parents or uncles was able to come to pick us up on Fridays, and we’d go home some weekends — not every weekend, but most times we were able to, especially when my family was at Deep River. Other kids never got to go home until June at the end of the school year.

I was pretty bright at school. I think a lot of times the teachers were quite surprised about how much I knew about current events, considering we lived in the bush and all we had was a little transistor radio. It definitely helped me in school, until toward the end when I got expelled because I was part of a group demonstrating. I ended up creating posters at the residential school and gave them to three cousins of mine. We were parading around there displaying these posters of these child abusers — one of them was a supervisor, and another was a clergy.

You see, in the residential school at the time they used to tell us “oh, you gotta practise so when you get older you know how to be with girls.” That whole concept, it was… I don’t know… it was not a good thing. When the lights went out at night, the boys would start creeping around and they’d end up crawling into your bed. You’re asleep, then you wake up and somebody’s bothering you. And you’d get threatened not to talk or make any noise. Eventually you start doing that yourself when you turn 14 or 15. Like I was saying, it was almost like we were made to practise.

But there was no love. There was no hugging. So, growing up as a young adult, I didn’t know how to hug. I didn’t know how to date. When I realized I was going to become an abuser myself, I realized how this went from being an abused to an abuser in a cycle. And I hated that. So, getting kicked out of the residence was a blessing in disguise because I got out of there, went on the trapline and made a living.”

Additional Resources

Ressources supplémentaires

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!